This is a long article, so to make it more manageable I will divide it into several installments and put a master-list here so you can jump to the sections (links will be added as I post):

- Introduction: Historical background and two main approaches to pattern-making (in this post)

- Materials and tools

- Pattern-making

- Shaping the fabric

- Cutting the fabric

- Adjustments and fitting issues

- Making the qipao (it’s loooonnng)

First, finished garment:

Now to the main:

Introduction

Qipao, as it is known today in Chinese Mandarin, is a type of dress for women that originated around 1920 in mainland China. Its exact origin is unclear and a subject of debate, as it bears resemblance to both the dress of the Manchus, the ruling ethnic group of the Qing Dynasty (approximately 1644-1912), and the Han, the ethnic majority of China. One possibility, discussed by Eileen Chang in her 1943 article ‘A Chronicle of Changing Clothes’, is that the Chinese women of the 1920s adopted changshan, a long gown worn by (both Manchurian and Han) men, in their pursuit of gender equality.[1] This would explain the alternative name for qipao, cheongsam, which is the transliteration of the Cantonese pronunciation of changshan.

Whilst qipao has been considered a ‘traditional’ garment of China, it actually mirrors the westernisation of China in the early twentieth century. Following the First Opium War and the Treaty of Nanking in 1843, foreign settlements established in port cities, particularly in Shanghai, and many aspects of Western, modern urban life were introduced to this city.[2] The modernist or abstract, geometrical prints on many qipaos provides one such example. In addition, Chinese women’s pursuit of gender quality, as reflected in the wearing of qipao, parallels the feminist movements in Europe and America of the same era.

In this article, I am going to introduce the construction of a qipao and outline the process of making a 1930s qipao. I will clarify the historical accuracy of a material or technique whenever possible.

- Two Main Approaches to Patternmaking

From the 1920s to the 1940s, qipao was widely adopted in mainland China, especially in major cities such as Shanghai. They were also popular amongst Chinese immigrant women in other parts of the world. After the 1950s, qipao continued to be worn outside mainland China, incorporating more tailoring techniques from the West, until its recent revival.

It would be useful to look at some defining characteristics of qipao that have been more or less consistent despite the changing of styles. In general, it has a standing collar that opens at the centre front. The opening then slants towards the right underarm and extends down the side seam. There is a separate strip of fabric sewn to the right side of the opening, under the opening and all the way from the neck to the bottommost button, which acts as a modesty panel and prevents exposure of skin during movement. A qipao is often fastened via knot-and-loop closures (or knot buttons and loops) on the right side and remains open at the bottom, which is matched by a slit at the left side. It was usually worn with a slip underneath, the lace trimmings of which will be visible as the lady moves. These characteristics are exemplified in this photograph of Ruan Lingyu, one of the most popular film stars of the 1930s (fig. 2a).

Figure 2a. Photograph of Miss Ruan Lingyu. 1930s. Author unknown.

In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in qipaoin China. The more traditional style, common before the 1940s, is called ‘flat cut (平裁)’ as it is not shaped via darts and the pattern is entirely two-dimensional. The later, more westernised design is often dubbed the ‘Hong Kong style (港工)’ as it was popular after the 1950s in Hong Kong as well as in other regions with Chinese communities, such as Singapore.[3]

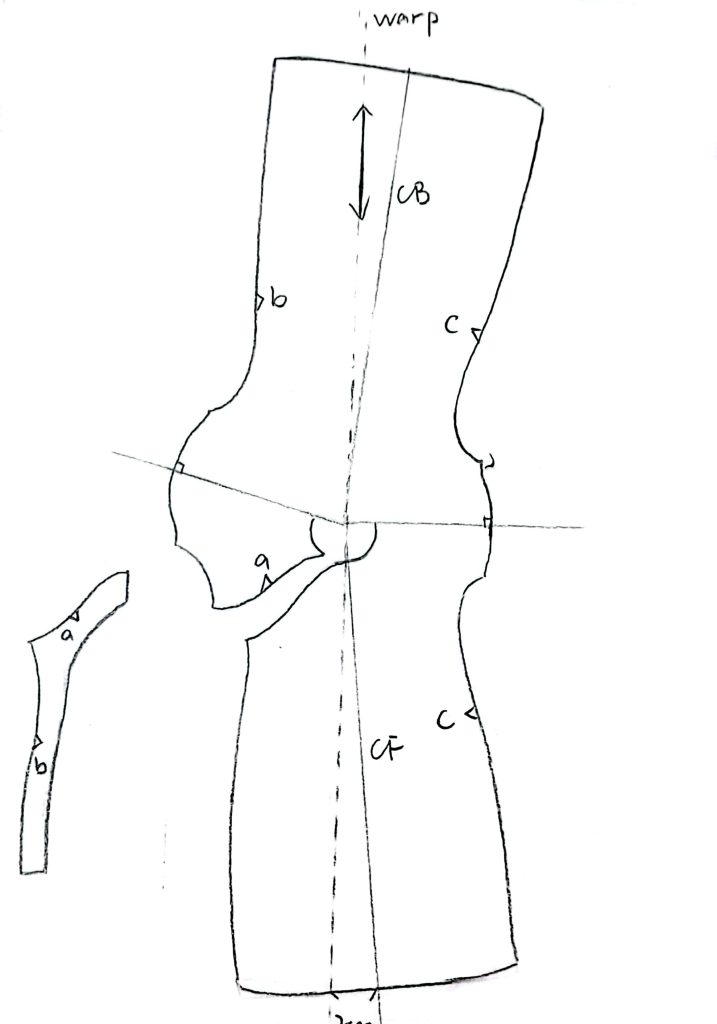

The ‘flat cut’ style has a smooth, flowy quality. Whilst the 1920s qipaos were commonly calf-length and rather relaxed, the 1930s styles were longer and hugged the body more closely, similar to the slender and elongated lines of the evening gowns in Paris of the same decade. There are two main characteristics for the ‘flat cut’ style. Firstly, there are no darts. Secondly, the entire qipao is cut in one piece, reflecting the availability of fabric with an increased width, as Qing clothes were still pieced with centre seams. Perhaps more importantly, the pattern puzzle presented here speaks to the confident manipulation of fabric. The seam between the modesty panel and the right side of the slanted opening should be just about hidden underneath the left side of the opening. This would be impossible to achieve if the centre front (CF) and centre back (CB) aligned exactly with the warp of the fabric and the shoulder lines the weft, since a small amount on each side is needed as seam allowance. Different ways to solve this problem rely on the same two principles. Firstly, one or more of the CF, CB and the shoulder lines is slightly slanted from the warp or the weft (Figure 2b). Secondly, the neck seam (where the collar is attached) is drawn asymmetrically, with the right side ending very slightly above the left side at CF. When the piece is cut and the sides are aligned, there would then be a small overlap of around 1-2cm at the slanted opening to serve as seam allowances.

Figure 2b. One way of arranging and cutting a qipao pattern. Note how the CF and CB slightly deviate from the direction of the warp (indicated by the double arrows), so that there could be enough fabric for the seam allowances at the diagonal neck opening. Made by author.

The ‘flat-cut’ style is more suitable for a small-chested wearer, as shaping is limited. In contrast, the Hong Kong-styled qipao is shaped via bust, waist and back darts to fit the body as closely as possible. The Hong Kong style often ends just below the knee and has higher slits, too. Zippers appear much more frequently on the Hong Kong style than on the earlier qipaos.

There is no impermeable line separating these two categories. Historically, methods of closure, decoration, the number and placement of darts, etc. would have been dependent on the factors such as the age and the body shape of the wearer, as much as the era and fashion.

- Design Options

Whilst a qipao most commonly opens from the neck to the right underarm, there are also other styles. For example, a qipao could have symmetrical front openings from the neck to the right and left underarms, although it still opens only down the right side. There is no need to slant the pattern in this design since the pattern is divided into a front piece and a back piece. Although there is insufficient evidence for a religious or cultural taboo, we usually avoid a slanted opening towards the left side only.

There are countless variations of bindings and edge decorations, with a range of confusing names. For our purpose, it will suffice to recognise the design possibilities of multiple rows of bindings and decorations (e.g. a narrow row sandwiched between two wide rows) combining binding with applique and piping.

For this article, I will be making a 1930s qipao with symmetrical front openings, due to the limit of the fabric I have. I plan to have one wide row of binding and a narrow strip between the wide binding and the main fabric. My qipao will be unlined.

Endnotes:

[1] Eileen Chang, ‘A Chronical of Changing Cloths’, translated by Andrew F. Jones, Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 11: 2 (2003), 435.

[2] Leo Ou-Fan Lee, Shanghai Modern (Harvard University Press, 1999), 7.

[3] Lee Chor Lin, In the Mood for Cheongsam (Editions Didier Millet, 2012), 9. It is unclear whether the names ‘平裁’ and ‘港工’ are academic terms. They are widely used according to my own observation.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.